My wife and I have been watching apocalyptic movies lately. Last week it was Planet of the Apes (speaking of which, check out this great post over on Medieval Meets World). This week it is The Omega Man.

I don't know what exactly prompted this apocalyptic interest. Probably it was the proliferation in culture of apocalyptic talk, related to the whole 2012 Mayan prediction thing. But regardless, of where the interest came from, it got me thinking about medieval apocalyptica. Now obviously theologically-minded or -oriented medieval writers wrote about the literal Apocalypse. Here is a book about it. But just like we do today, medieval folks told stories about all kinds of things. The Middle Ages encompasses a very very long time (most folks think of it as about 500-1500 CE), and during that time there were certainly moments of intense cultural anxiety about the end of the world--moments of at least as much cultural attention as 2012 has for us. So is there any medieval apocalyptic fiction? When medieval writers told stories about the end of the world, what did those stories look like?

My central scholarly interest is Thomas Malory's Morte Darthur, which is a very late medieval work (from about 1485). Because I already spend a lot of time thinking about the Morte Darthur, it is the first thing I think of now, too. The Morte definitely has apocalyptic overtones. For the characters within the artistic frame, the death of Arthur and the fall of the Round Table are very much like the end of the world. The fellowship dissolves, and all of the knights end the story either dead or in a hermitage, in retreat from the world. In its way this is as apocalyptic as any movie like Planet of the Apes. Malory spends most of his time constructing this world, but his story has always been inexorably1 leading toward this end. The title of the book, after all, is Le Morte Darthur2. It is, from the very beginning, from even before Malory relates Arthur's conception, about Arthur's death. It is about the end of a world.

100 years earlier, Gower's Confessio Amantis, which was written basically at the same time as and which shares much in common with Chaucer's Canterbury Tales3, including several of the stories, is4not a particularly apocalyptic text in and of itself. It's the story of a worshiper of Venus making his confession. The priest (of Venus) to whom he is confessing preaches to Amans, and tells him a series of stories about the 7 deadly sins5. The stories themselves, as I have said, are not particularly apocalyptic. But Gower's prologue, in which he retells and interprets the story of Nebuchadnezzar's dream. The dream is of a statue with a head of gold, arms of silver, a torso of brass, legs of steel, and feet of steel mixed with clay. Daniel6 interprets the dream as a prophesy of ages to come. Each empire is followed by a weaker one, until the last--the feet of clay--which brings the whole statue down. Gower is quite sure that his day is the day of the feet of clay.

200 years7 before that, Beowulf is as apocalyptic as any monster movie of today. The first two parts of Beowulf, in which king Hrothgar and his Danes are being attacked in the night first by a monster named Grendel, who comes out of the darkness and carries away the men one-by-one and then by Grendel's lake-monster mother, are perhaps better described as "near-apocalyptic", since the hero Beowulf successfully prevents the end of the world8. The third part, in which Beowulf is himself killed while fighting and killing a dragon, is apocalyptic in almost exactly the same sense as the Morte Darthur is9. Beowulf dies and with him dies his world.

This isn't, by the way, just a case of pathetic fallacy like the Fisher-King, wherein the land suffers with the king. Beowulf the king was Beowulf the warrior--strong and famous enough to protect his people not only from monsters but also from warring nations. Without him, they are left vulnerable.

"swylce giómorgyd Géatisc ánméowle

Bíowulfe brægd bundenheorde

sang sorgcearig· saélðe geneahhe

þæt hío hyre hearmdagas hearde ondréde

wælfylla worn werudes egesan

hýðo ond hæftnýd." (Beowulf, lines 3150-3155)

A rough paraphrase of the above:

"A Geatish woman sang a lament for Beowulf because she was afraid of the very bad stuff that was coming."10

So there you have it. A rough and dirty look at some highlights of apocalyptic fiction from the Middle Ages. Concern about the end of the world is, unsurprisingly, a very old thing. It makes sense. We all live at the very end of time.

__________________

1 Well ... not exactly. Not necessarily. Some critics have argued that Malory didn't write one story, he wrote a collection of stories that don't necessarily lead to one another. But those critics were wrong.

2 It's not at all clear that Malory himself intended the book to be entitled Le Morte Darthur. More likely it was his publisher, William Caxton, who gave it that title. But still.

3 The Confessio Amantis was actually dedicated to Chaucer, and the two were friends. Or at least they knew each other well. If you believe Chaucer's blog, then "friends" doesn't exactly seem like the right term"

4Sorry about that. I have a bad habit of separating the subject from the verb. I do the same thing in speech. It drives my wife bonkers.

5Except for "lust", which obviously isn't a sin against Venus. Gower substitutes "incest". Because that is a reasonable substitution to make.

6Of the Bible, in case that wasn't clear to anyone.

7Or so. Maybe as much as 800 years, really.

8Or the end of Heorot. Whatever.

9Except, of course, that it was written way before the Morte was. So really the Morte is like Beowulf.

10I said it was rough.

I don't know what exactly prompted this apocalyptic interest. Probably it was the proliferation in culture of apocalyptic talk, related to the whole 2012 Mayan prediction thing. But regardless, of where the interest came from, it got me thinking about medieval apocalyptica. Now obviously theologically-minded or -oriented medieval writers wrote about the literal Apocalypse. Here is a book about it. But just like we do today, medieval folks told stories about all kinds of things. The Middle Ages encompasses a very very long time (most folks think of it as about 500-1500 CE), and during that time there were certainly moments of intense cultural anxiety about the end of the world--moments of at least as much cultural attention as 2012 has for us. So is there any medieval apocalyptic fiction? When medieval writers told stories about the end of the world, what did those stories look like?

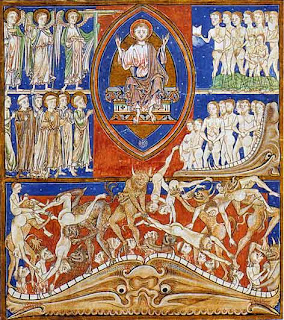

|

| Something like this? |

My central scholarly interest is Thomas Malory's Morte Darthur, which is a very late medieval work (from about 1485). Because I already spend a lot of time thinking about the Morte Darthur, it is the first thing I think of now, too. The Morte definitely has apocalyptic overtones. For the characters within the artistic frame, the death of Arthur and the fall of the Round Table are very much like the end of the world. The fellowship dissolves, and all of the knights end the story either dead or in a hermitage, in retreat from the world. In its way this is as apocalyptic as any movie like Planet of the Apes. Malory spends most of his time constructing this world, but his story has always been inexorably1 leading toward this end. The title of the book, after all, is Le Morte Darthur2. It is, from the very beginning, from even before Malory relates Arthur's conception, about Arthur's death. It is about the end of a world.

100 years earlier, Gower's Confessio Amantis, which was written basically at the same time as and which shares much in common with Chaucer's Canterbury Tales3, including several of the stories, is4not a particularly apocalyptic text in and of itself. It's the story of a worshiper of Venus making his confession. The priest (of Venus) to whom he is confessing preaches to Amans, and tells him a series of stories about the 7 deadly sins5. The stories themselves, as I have said, are not particularly apocalyptic. But Gower's prologue, in which he retells and interprets the story of Nebuchadnezzar's dream. The dream is of a statue with a head of gold, arms of silver, a torso of brass, legs of steel, and feet of steel mixed with clay. Daniel6 interprets the dream as a prophesy of ages to come. Each empire is followed by a weaker one, until the last--the feet of clay--which brings the whole statue down. Gower is quite sure that his day is the day of the feet of clay.

200 years7 before that, Beowulf is as apocalyptic as any monster movie of today. The first two parts of Beowulf, in which king Hrothgar and his Danes are being attacked in the night first by a monster named Grendel, who comes out of the darkness and carries away the men one-by-one and then by Grendel's lake-monster mother, are perhaps better described as "near-apocalyptic", since the hero Beowulf successfully prevents the end of the world8. The third part, in which Beowulf is himself killed while fighting and killing a dragon, is apocalyptic in almost exactly the same sense as the Morte Darthur is9. Beowulf dies and with him dies his world.

This isn't, by the way, just a case of pathetic fallacy like the Fisher-King, wherein the land suffers with the king. Beowulf the king was Beowulf the warrior--strong and famous enough to protect his people not only from monsters but also from warring nations. Without him, they are left vulnerable.

"swylce giómorgyd Géatisc ánméowle

Bíowulfe brægd bundenheorde

sang sorgcearig· saélðe geneahhe

þæt hío hyre hearmdagas hearde ondréde

wælfylla worn werudes egesan

hýðo ond hæftnýd." (Beowulf, lines 3150-3155)

A rough paraphrase of the above:

"A Geatish woman sang a lament for Beowulf because she was afraid of the very bad stuff that was coming."10

So there you have it. A rough and dirty look at some highlights of apocalyptic fiction from the Middle Ages. Concern about the end of the world is, unsurprisingly, a very old thing. It makes sense. We all live at the very end of time.

__________________

1 Well ... not exactly. Not necessarily. Some critics have argued that Malory didn't write one story, he wrote a collection of stories that don't necessarily lead to one another. But those critics were wrong.

2 It's not at all clear that Malory himself intended the book to be entitled Le Morte Darthur. More likely it was his publisher, William Caxton, who gave it that title. But still.

3 The Confessio Amantis was actually dedicated to Chaucer, and the two were friends. Or at least they knew each other well. If you believe Chaucer's blog, then "friends" doesn't exactly seem like the right term"

4Sorry about that. I have a bad habit of separating the subject from the verb. I do the same thing in speech. It drives my wife bonkers.

5Except for "lust", which obviously isn't a sin against Venus. Gower substitutes "incest". Because that is a reasonable substitution to make.

6Of the Bible, in case that wasn't clear to anyone.

7Or so. Maybe as much as 800 years, really.

8Or the end of Heorot. Whatever.

9Except, of course, that it was written way before the Morte was. So really the Morte is like Beowulf.

10I said it was rough.